Want to Paint Like Raphael?

The Forgotten Process of Renaissance Mastery

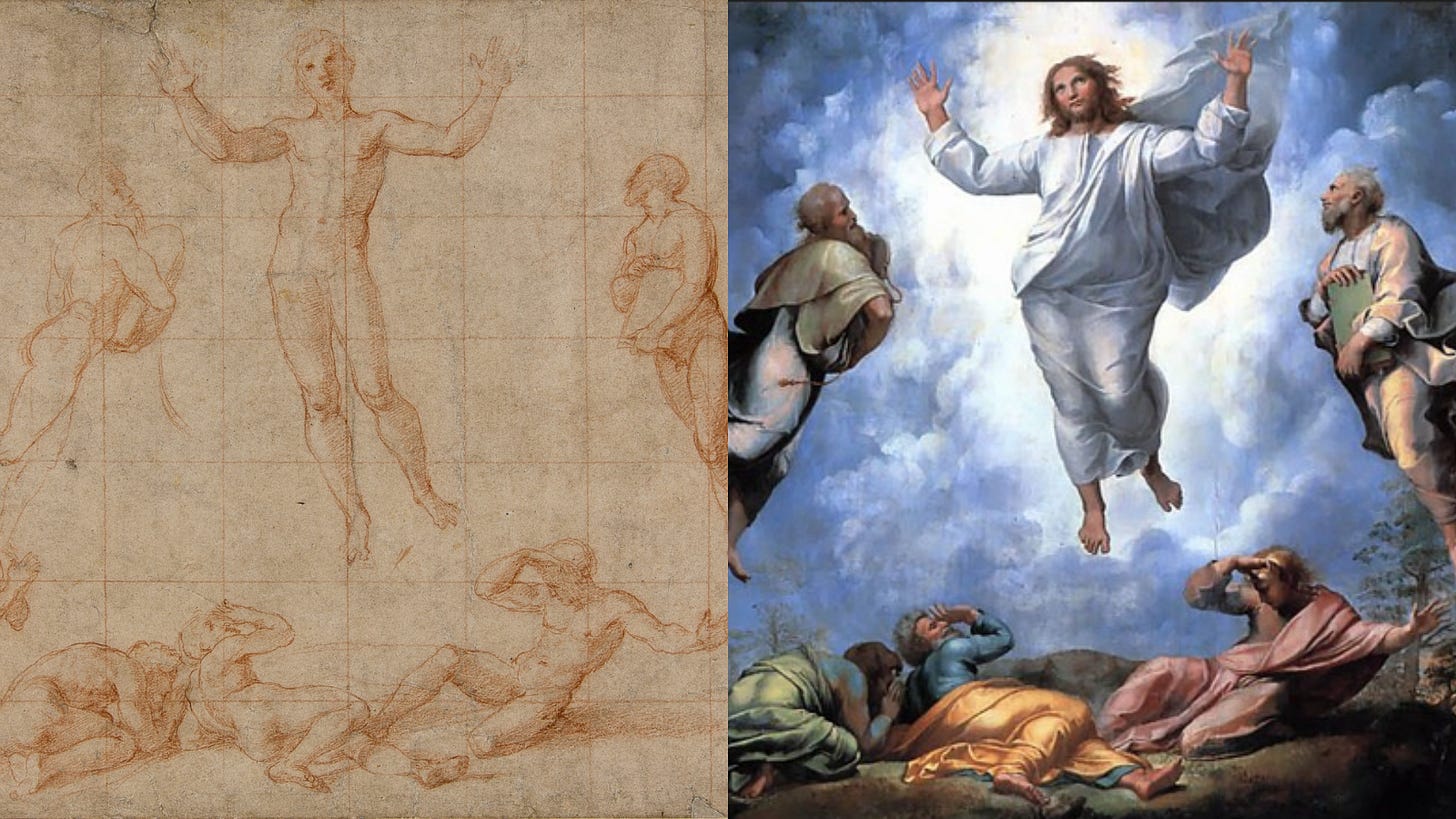

Imagine standing in front of The Transfiguration. You feel the harmony, the precision, the divinity of each figure - Jesus, Moses, St. Peter - seemingly effortlessly positioned in perfect perspective.

Now imagine creating something like that. Where would you even start?…

It’s easy to look at a Raphael and think: Genius. He simply dipped his brush into paint and conjured divine beauty from instinct.

Wrong.

But here’s the truth- Raphael didn’t wing it.

He engineered his paintings like cathedrals.

Behind every one of his masterpieces was a hidden blueprint - a method so meticulous, so multi-layered, that each stage had to be built with intention and patience and most importantly… Love. If you’ve ever wanted to paint like a Renaissance master, the secret lies not just with paint on a brush... but more importantly, in everything that happens before it ever touches the surface.

Let’s reverse engineer how Raphael painted.

Contrary to popular belief, artists like Raphael never started with the painting itself. The first step was always the cartoon (a full-scale preparatory drawing.)

This wasn’t a quick sketch. It was the architectural blueprint for the painting which would sometimes take months to complete.

Every figure, gesture, and architectural detail was worked out in charcoal, chalk, and sometimes ink. A cartoon was both a planning tool and a visual rehearsal - allowing Raphael to choreograph the composition and correct proportions before a single stroke of paint ever touched a surface. In fact, in Italian disegno is the word for ‘draw'/design’ and is related to our English word of design.

Entire studios of assistants spent days refining a cartoon under his supervision- often redrawing parts based on the master's corrections or guidance.

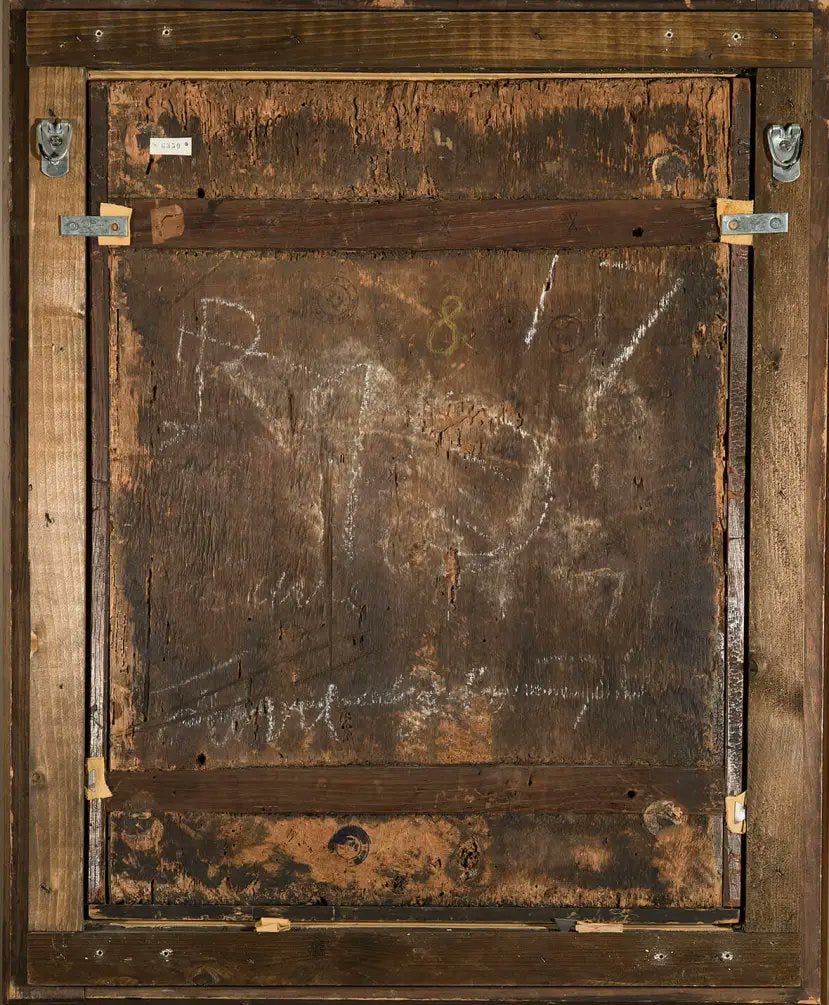

Once the drawing was finalized, it was ready to be transferred to the painting surface. But the surface itself wasn’t just a blank canvas. It was a work of craftsmanship in its own right.

Most of Raphael’s paintings were done on wooden panels, not canvas. He typically used poplar wood which is a soft but stable wood favored by Italian painters.

But here’s where a little bit of science comes into play.

The wood had to be prepared with exacting care to prevent warping or cracking over centuries. Panels were joined together using calcium caseinate - a glue made from casein (milk protein) and lime. To strengthen the structure, cross beams were inserted across the back.

After the structure was in place, the surface would needed to be sealed…

A layer of animal glue (typically rabbit skin glue) was brushed onto the wood. This penetrated the fibers and created a base for what would come next- the gesso ground.

But this isn’t the stuff we find in stores today. The Renaissance version was way cooler.

The priming layer applied on top of the glue was a mix of calcinated plaster (a type of lime), more animal glue, and in some cases- powdered glass.

Why powdered glass you may ask?

Because it subtly refracts light, giving the painting a luminous inner glow. Think stained-glass windows, but in pigment form. The entire mixture was applied in thin layers, then scraped and polished to a silky smooth finish.

The powdered glass created a physical and optical foundation that would interact with every layer of paint to come. The light, coming through the various layers of pigment would eventually reach the white gesso layer and then reflect back to the viewer through the powdered glass. Raphael would was even known to add powdered glass to his pigments from time to time.

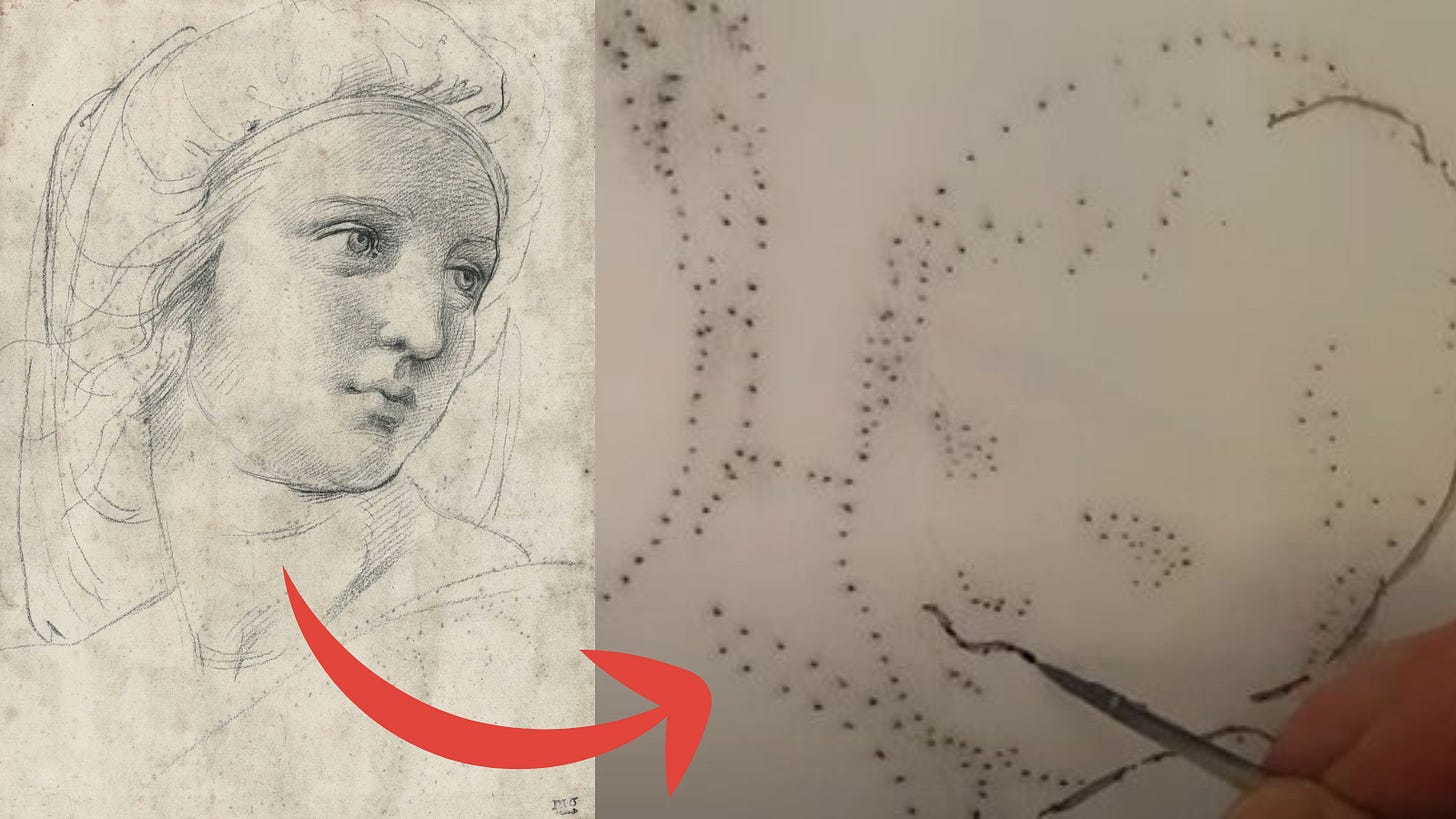

But how did Raphael get his cartoon (the masterful drawing) onto the drawing surface in the first place?

The cartoon would be pierced along all the major outlines with a pin or needle. Then it was placed on the panel. A sack of charcoal dust was patted (pounced) across the surface, pushing pigment through the holes and onto the gesso.

When the cartoon was removed, it left behind a faint dotted outline of the composition.

Raphael (or more likely, an assistant) would then go over these lines with a thin brush of diluted black pigment, locking in the underdrawing.

The outlines were just the beginning.

He’d then use hatching strokes (light, parallel brushstrokes) to indicate shadows, volumes, and sometimes even background tonal values.

The image was now set.

Next came one of the most crucial steps...