The Book That Survived Fire and Transformed Asia: Confucius' Analects

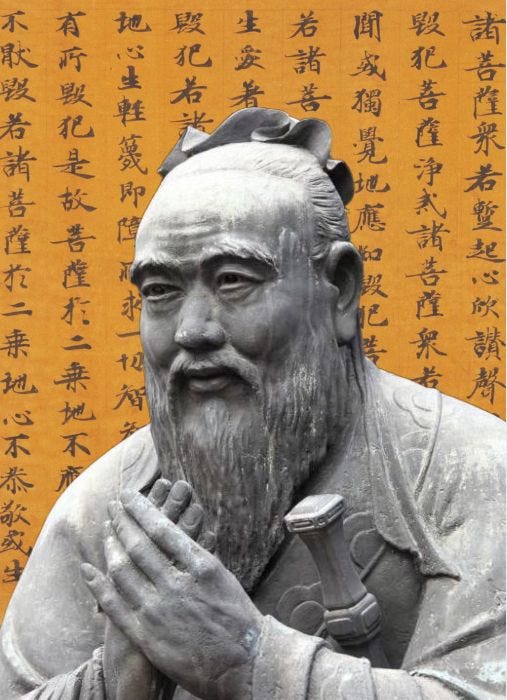

Two thousand years ago, a teacher without an army changed the course of history - not by conquering kingdoms, but by sculpting minds.

Confucius lived during one of China’s most turbulent eras—the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BC). Central authority was dissolving. Local rulers were jockeying for power. Civil war was a constant threat. The old rituals that once bound society together were being hollowed out by corruption and ambition for power.

In this chaos, Confucius was born in 551 BC to a once-noble family fallen on hard times. He studied history, music, and ancient rites. He revered the Zhou Dynasty’s golden age, when ritual and virtue supposedly governed society. But he wasn’t content to simply admire the past—he wanted to revive it.

Confucius became a teacher, an advisor, a wandering sage. He traveled from state to state, offering counsel to rulers. His message was simple but demanding: rule by virtue, not force. Lead by moral example, not law or punishment.

He was mostly ignored. Sometimes mocked. Even betrayed.

But wherever he went, he attracted students—men drawn to his teachings, but more importantly to his character. His followers recorded his sayings, debated his ideas, and after his death, compiled them into a text that would eventually be called The Analects (from the Greek analekta, “things gathered up”).

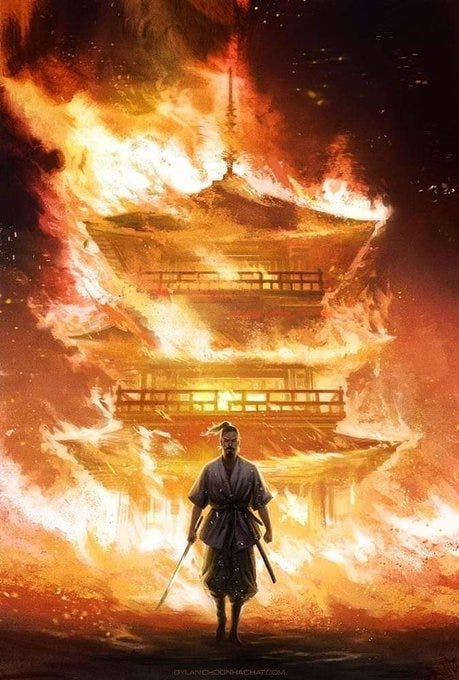

By the 3rd century BC, China was once again in the throes of political transformation. The Qin Dynasty, led by the iron-fisted Emperor Qin Shi Huang, succeeded in unifying the warring states. But this unification came at a grave cost.

To consolidate power, Qin ordered a sweeping campaign to destroy any writings that did not align with his vision of order. Philosophy, poetry, historical records—whole libraries were burned. Scholars who resisted were executed or buried alive.

Confucianism, with its emphasis on ethical rule, loyalty to the past, and the moral authority of scholars, posed a direct threat.

The Analects should have vanished in the flames.

And yet, it didn’t.

Some copies were hidden inside walls. Others were preserved through oral transmission. Fragmentary versions survived in private collections. Later scholars worked to piece the text back together from memory, family archives, and scattered scrolls.

The version we have today is not a perfect record. It is a patchwork of sayings, student notes, and interpretations—20 short chapters of dialogues, observations, and cryptic wisdom. But despite the gaps and centuries of editing, its voice is unmistakable.

At its core, The Analects rests on a radical premise: the health of a society is not determined by its laws or armies, but by the moral character of its people—especially its leaders.

This is why Confucius compares virtuous leadership to the north polar star:

“He who governs by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which remains in its place while all the stars revolve around it.” (Analects 2.1)

In a world obsessed with strength and obedience, this was a quiet rebellion. Confucius proposed that influence flows from example. That the best leaders don't shout—they embody virtue. A trait which is sorely lacking in most government institutions today.

There are two concepts which anchor Confucian ethics: li (禮) and ren (仁).

Li is often translated as “ritual,” but that doesn’t really do it justice. Li includes formal ceremonies, yes, but also gestures of respect, social etiquette, even tone of voice. It's how you greet someone. How you pour tea. How you respond to a parent, or a stranger, or a grieving friend. Basically everything.

In essence, li is the choreography of daily life—it’s how civilization is lived moment by moment.

But Confucius knew that ritual alone could become empty performance. That’s where ren comes in.

Ren is harder to define. Sometimes rendered as “benevolence” or “humaneness,” it points to an inner warmth, a capacity for empathy, a deep regard for others as fellow human beings.

“Only the humane person is able to truly love others or to truly despise them.” (Analects 4.3)

Ren gives li its Soul. And together, they create a model of behavior that is at once highly structured and deeply human and which has lasted thousands of years.